Over the course of ten artist interviews during season one of the podcast, a range of approaches to making money as a creative person is explored (other than being a full-time artist, of course, the point of the podcast being the dynamic between the work we do for pay and the work we do for “love”). Some artists, like Elizabeth Amento, preferred, at least at the time of our interview, that their day job be completely separate from their art practice, preserving that creative brain space for precious studio time. Other artists, like Janine Biunno, expressed a need to support themselves financially in a way that was more closely aligned with their creative interests. As someone who has always longed for more studio time (even when I wasn’t working for pay between 2017 to 2019 I was very much working as a stay-at-home parent and volunteering a lot more then than I do now), I naturally envy artists who manage to avoid the day job altogether, although I acknowledge that some of those creative revenue streams must start to feel like a day job at some point and that certainly has its own pros and cons (to wit, a recent newsletter update from Marlee Grace explores exactly this phenomenon). After all, we call it “work” for a reason. At this midlife point as a creative person, I’ve dabbled in just about every combination of the art/work/life balance: self-employment, full-time day job in an adjacent field, unemployment-by-choice/stay-at-home parenthood, part-time gig(s) (20-40+ hours a week), and, most recently, a full-time role in a mostly unrelated field.

Working as a part-time training coordinator turned full-time program manager at a tech company is the latest in a “portfolio” of day jobs I’ve had over the past 25 years (I’ve written about most of those jobs here). This might seem like a bit of a pivot for a visual artist whose education and experience has otherwise been rooted in art and design, but the role has been, for the most part, a surprisingly good fit. After all, the company’s motto is “the world is a better place with more creators in it.” I don’t disagree. For folks in the art world, I usually liken what Unity has done for video game development to what Theaster Gates has done as an artist in and for his community and beyond: “Making the thing is cool,” he has said, “but to be able to make the thing that makes the thing is supercool” (emphasis mine). Being part of a company that empowers other creative folks to make things, even if those things are different from my own creative output, has indeed been pretty cool.

That said, the overlap between the work I do for pay and my creative interests is somewhat limited. Shortly after the pandemic began, less than a year into my first, part-time role at Unity, I saw Ian Cheng’s BOB (Bag of Beliefs) at the recently reopened de Young Museum in San Francisco. When I learned that Cheng created BOB—the first in a series of artificial lifeforms who takes the form of a chimeric branching serpent—using Unity, I was intrigued to research other visual artists using real time 3D technology as a creative medium. Fast forward three years, I’ve since transitioned to a full-time role, leaving less time for my creative pursuits, perhaps motivating me to find greater alignment with the work I do for pay, since I now spend most of my time in that capacity. Which you might understandably assume means I started to learn to use Unity myself. Not quite, still preferring to tinker in my studio with materials like wood, paint, felt, and yarn. Instead, I was and am interested in showcasing the growing field of artists working in this way, often in collaboration with a programmer. Over the past three years, I’ve compiled a lengthy working document with links to examples, press, events, workshops, and so on. Earlier this year, emboldened by a personal connection to one of them, I decided to reach out to three of these artists, Cheng among them, and the Unity developer who collaborated with all three to learn more about how this kind of work gets made and shown.

“It’s very difficult to know exactly whether to live for an ideology or even to live for doing good. But there cannot be anything wrong in making a pot, I’ll tell you. When making a pot you can’t bring any evil into the world.”

These days, Unity customers can, generally speaking, be placed in one of two broad categories: entertainment or industry. While Unity has become synonymous with video games since its founding in 2004, real-time 3D technology has more recently been embraced by many other industries as well, including fine art. Unity’s Social Impact division showcases and supports many of these creators, of course, but this growing “use case” is much more vast than one might imagine. As if in response to the more recent expectation that art save the world, I adore the above quote by Hungarian-born American industrial designer, potter, and ceramist Eva Zeisel (1906-2011), interviewed by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi for his book, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention, in which he elaborates on his earlier theory of flow applied in this book to the broader field of creativity, which he defines in part as "the attempt to expand the boundaries of a domain.” Not unlike the guidelines and goals of the Unity for Humanity grant program, the motto at my last full-time day job was something like “make art that matters.” And while I’m obviously not opposed to the world-changing potential of art, I worry that we miss out on a lot of creatively and technically innovative work when we impose unnecessarily narrow constraints on where we shine our spotlight. What I found simply by looking around and doing some digging is that artists working at the intersection of art and technology leverage Unity’s tools, among others, to do just this: creating work that expands the boundaries of the domains of art and technology and the very definition of creativity itself.

The distinction between video games and fine art is an increasingly fuzzy one. World Building, an art exhibit at the Julia Stoschek Collection in Düsseldorf that opened in June 2022, examined how games have become increasingly prevalent in our visual culture, the language of games allowing artists to imagine a more diverse and inclusive world. The interactive storytelling capabilities of XR have been embraced by creators in the film industry as well. In 2019 the Tribeca Film Festival launched the Tribeca Immersive to showcase such innovations (the LGBTQ+ Museum, co-created and directed by Unity’s own Antonia Forster, was an official selection of the 2022 festival). If you’re in San Francisco you can view artist Wu Tsang’s Of Whales, made with Unity, for free in the lobby of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Of Whales is an immersive real-time video and sound installation based on Tsang’s research around Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick. Fashion label Louis Vuitton recently collaborated with artist Yayoi Kusama using Snap AR to virtually decorate six landmarks with Kusama's trademark dots. More traditional artists have found ways to incorporate this technology as well, such as Oakland-based artist Lisa Kairos, a painter who added a digital layer to three of her recent paintings using Artivive, an AR app made with Unity. Fine art has made its way into games as well. Pentiment, a 2022 video game made with Unity, has been described as a video game made by art history buffs for art history buffs.

While visual art made with Unity is attracting more attention these days, it turns out Unity has been quietly leveraged in unconventional and inventive ways by artists, creative technologists, and digital designers from very early on. After all, visual artists are historically some of the earliest adopters of emergent technologies, often recruited by the companies creating these new tools to experiment with them. Copier art, for example, is an art form that began in the 1960s largely out of a collaborative partnership between companies like Canon and Xerox and artists like Esta Nesbitt, whose creative research was sponsored by Xerox Corporation from 1970 to 1972 and resulted in the invention of additional xerography techniques. Nesbitt and other copier artists expanded the boundaries of xerography technology, not unlike how visual artists since the early 2010s have leveraged Unity tools and a community of programmers to push the boundaries of real time 3D development in unexpected ways.

One programmer, three artists.

“I really got a lot of joy out of the labor of helping to make these kinds of projects, being able to write some code and have that lead to a really interesting animation, or a shader effect that I haven't seen. Having this immediate feedback between the code I was writing and something meaningful to me happening on screen was really revelatory. It felt really different from the kind of work I’d done before.”

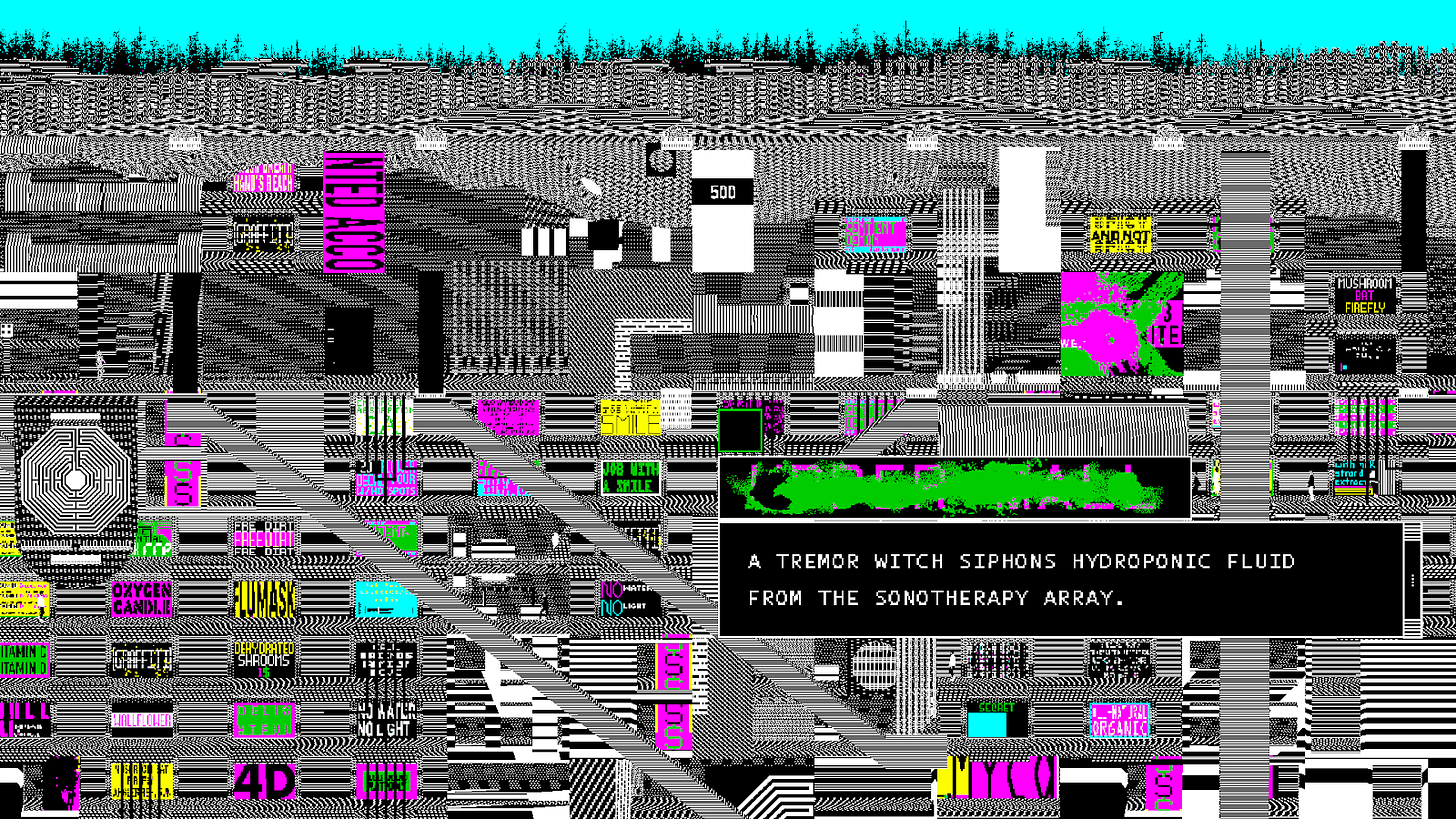

Oren Shoham is a creative technologist who, in addition to freelance work for various corporate customers, has worked as a Unity developer in collaboration with a number of visual artists. After college, where he majored in Computer Science, Shoham completed a residency at The Recurse Center, a self-directed, community-driven educational retreat for programmers in New York. It was at The Recurse Center that Shoham became aware of the wider community of artists working with code and what he describes as “alt programmers” working in this space. Later, in a class about live video performance at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts, where Shoham was pursuing a Master of Professional Studies degree in Interactive Telecommunications, he met guest lecturer Peter Burr, a digital and new media artist based in Brooklyn, New York, whose practice often engages with tools of the video game industry in the form of immersive cinematic artworks. About Burr’s Dirtscraper, a feature-length immersive interactive installation made by Burr using Unity before the two started working together, Shoham says, “I’d never seen an animator like Peter before. I’d never encountered that kind of work. As soon as I saw it I knew I wanted to do something like that or at least understand more about how one comes to make that kind of work.”

A real-time 3D palette

Burr was exposed to the tools of game design as a student at Carnegie Mellon University, but didn’t really consider video games as a creative medium until much later, around the time he discovered, through an essay on the digital art and culture website, Rhizome, the indie video game Kentucky Route Zero, a point and click adventure game made with Unity developed by art school graduates. “Being exposed to that made me realize that I could do something I was interested in with this technology.” At the time, due in part to the heavier technical lift of working with a tool like Unity, Burr’s creative work in newer technologies focused in painting and installation, occasionally looking to the Unity community to find the solution to a specific problem—for example how to add a dither shader—or someone to help him with the technical aspects of his work when resources allowed. A Creative Capital grant in 2015 provided him with the resources to collaborate with a Unity developer like Shoham.

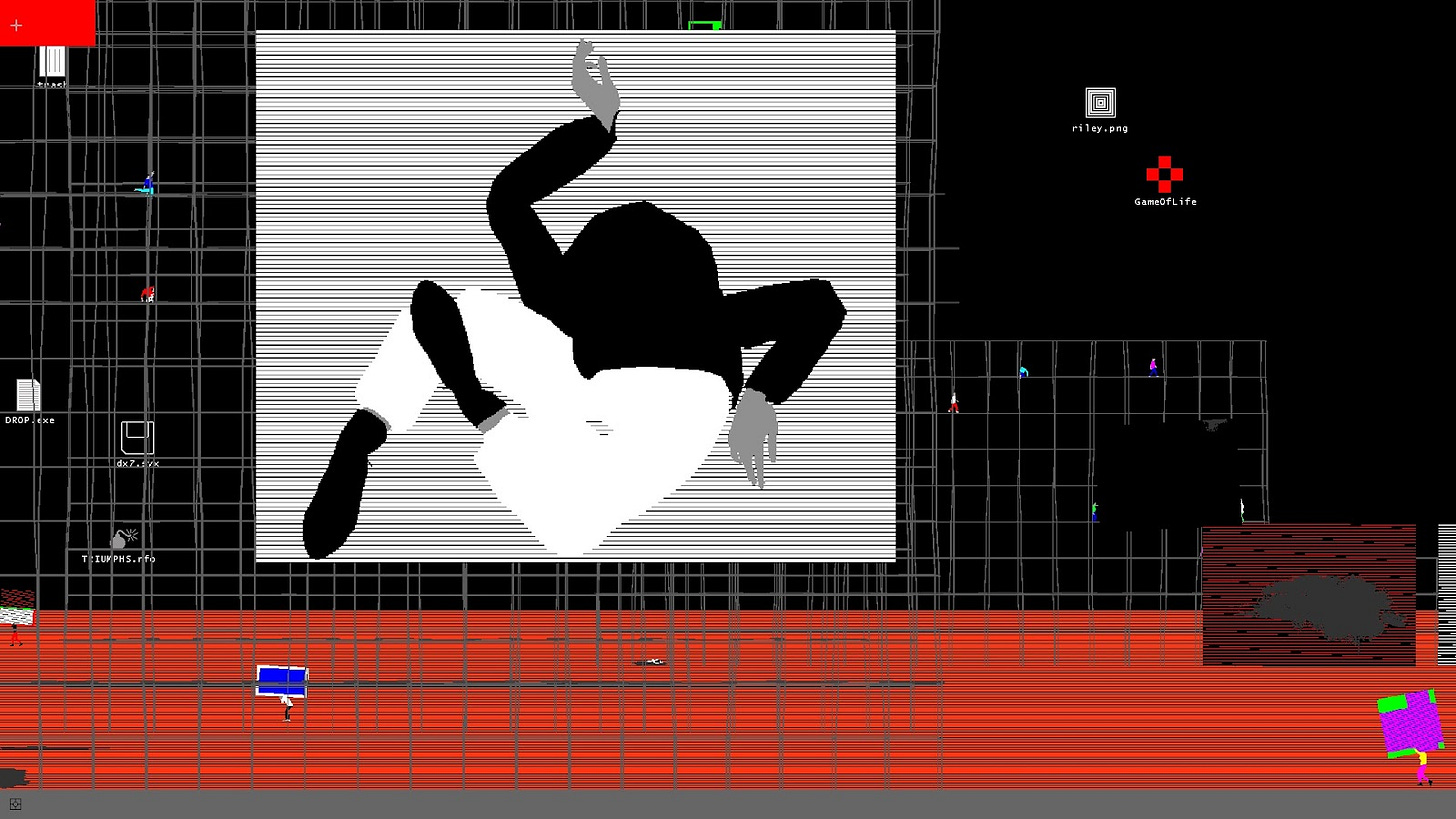

Shoham and Burr connected and over time developed a creative partnership, even sharing a studio at one point, with Shoham initially working with Burr on Drop City, commissioned by Daata Editions in 2019. Drop City, Shoham’s first Unity project, is a portrait of a computer desktop community that takes its name from the first rural commune in America, formed in 1965 and completely abandoned a decade later. For Drop City, Shoham programmed crowd simulation agents and procedural character animations. Burr and Shoham have since collaborated on a number of creative projects, with Shoham creating a custom Unity toolkit Burr can use independently. Shoham explains, “Now that we've made a system that we like, how can I make it so Peter can use it, even if I'm not around? How can he adapt it, tweak it? What parameters can I expose for him that will allow him to use this as a tool to make his art rather than just a generator.”

“When you’re working in a game engine you're building up these custom tools to create these elaborate environments. Because it's all digital, even if it doesn't come to fruition, it's never time wasted because it's always there for you to go back, and flip an asset in a different way, or change some variables in the shader, and all of a sudden it creates a very different effect. It's a palette that you can reconfigure or revisit over the years.”

Currently, Burr is a PhD candidate in the Critical Game Design program at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the only visual artist currently in the program, which is designed to “graduate entrepreneurial, critical-theory savvy game developers who work to change the face of games research and the games industry”. In a post-COVID world, Burr is interested in reimagining how we can use these tools to come together again in a different capacity. “What is produced when you're using these tools that artlessly, endlessly dream new stories? This highlights the importance of artists who are operating outside of market forces, artists who are making work from a different space, from a different sort of imagination, trying to dream what's not yet been dreamed.”

World Building, World Watching

Through a mutual acquaintance, Shoham later connected with Ian Cheng, high on Shoham’s list of artists he wanted to work with, known for his live simulations that explore the capacity of living agents to deal with change. Cheng studied Art Practice and Cognitive Science at the University of California at Berkeley. After college, Cheng worked at Industrial Light & Magic for a year before moving to New York to pursue a Master of Fine Arts degree at Columbia University, where he worked with artists like Pierre Huyghe and Paul Chan. Cheng points to Sim City as the first video game to inspire him to care about systems and social dynamics, something he aims to do in his own creative work. Using Unity allows him to “care about animation” while directing more of his attention as an artist to “what animation is serving: a story, a system, a simulation, a scenario.” Cheng described an experience he had shortly after graduate school, eating lunch at a Whole Foods in New York, overlooking the prepared foods area below. He described the experience “like watching squirrels at the park” and how it inspired him to try to recreate this unique quality of attention. “I could watch this for hours or five minutes,” which is not unlike the temporal experience of looking at art in an exhibition setting. Cheng researched how to recreate this, as he describes it, “aliveness,” and that research led him to the Unity community.

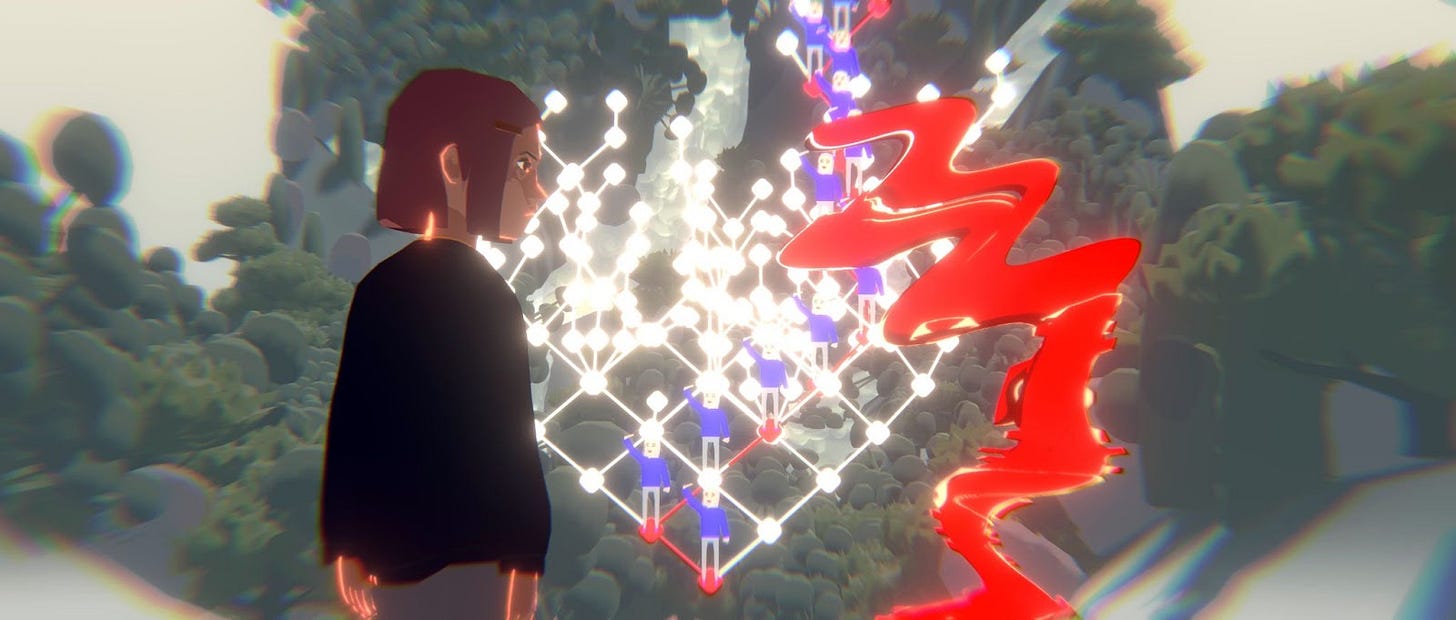

Learning by doing, Cheng initially worked on projects himself, learning C# programming and occasionally finding Unity assets and modifying them depending on what he wanted to do. With BOB (Bag of Beliefs), noted above, Cheng began to work with a producer and a larger team. “Only in a real time environment,” Cheng explained, “could I still be an artist” since Unity’s real time technology allows Cheng to make changes that would be highly impractical in a more traditional production environment. For Life After BOB: The Chalice Study, an episodic anime series made with Unity and presented live in real time, imagining a future world in which our minds are co-inhabited by AI entities, Shoham was brought in after almost all of the character animation and voice acting were done to help with the interactive framing of the project. Shoham worked on the World Watching mode, creating a custom tool in Unity to index every object and character in the film and made a database as well as a media wiki instance of the film linked to that database. “More and more,” Cheng says, “we have the opportunity technologically, if not yet artistically, to try to make mediums where you can flicker much more fluidly between the narrative…and the world,” not unlike that formative experience of watching shoppers at Whole Foods.

Rendering Point Cloud Data in the Cloud

“I work collaboratively with the artist to find the questions that we need to ask and then it's my job to go off and answer that question of how do we do that?”

The process for Shoham’s collaborative way of working varies from artist to artist and depends somewhat on other circumstances as well. Because they shared a studio at one point, Shoham and Burr have at times been geographically collocated, literally rolling their chairs back and forth across the studio to share an idea or progress with one another. For Cheng and artist Nica Ross, with much of the work taking place during the various lockdown periods of the pandemic, the process was much more virtual, using various cloud-based tools to collaborate.

“Working with Nica [Ross] was really great. They were very supportive of me trying something I wasn’t quite sure how to do in order to accomplish their goals for the project.”

Nica Ross is an artist based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, whose creative research, across video installation, performance, gayming, sporting, and more, challenges normative ideologies and social constructions that are reinforced by technology, performance, and play. While Permanent Visibility is their only project made with Unity so far, “the vernacular of gaming,” they explained, “is something that is throughout my work.”

Ross, a friend of Burr’s, was looking for a developer to help with Permanent Visibility, a VR project based on raw point cloud data generated by sensor-free motion capture in Carnegie Mellon University’s Panoptic Studio. “The raw data,” Ross explained, “showed this messy impression that machine vision is getting and I wanted to show that, so I wanted to play it back. Unity was the only tool that was available that could do this.” Shoham collaborated with Ross on the project, rendering the point cloud data in Unity and building custom timeline integrations in order to sequence the motion capture as they were designing the project Ross refers to as a virtual reality based essay that celebrates the failure of surveillance and nonhuman vision when applied to the human form. For this project, Shoham relied heavily on the work of one of Unity’s Senior Advocates, Keijiro Takahashi, described by Shoham as “constantly pushing the technical boundaries of what kind of creative artistic work can be done and often publishing his work at open source for other developers to iterate on or use as reference material,” specifically, in this instance, “a point cloud renderer for Unity that worked with the file type that Nica had.”

“A programmer is a diviner of possible outcomes, and a seer of unseen worlds.”

The collaboration between artist and programmer to realize these creative projects made with Unity is not unlike the relationships that Ross witnesses as an educator. “There's a really interesting dynamic in some of the classes I teach where there are people who are toolmakers and people who are conceptual makers. The toolmakers are oftentimes like, ‘I made this really wild tool, and now, I really want to work with somebody who's going to use it, so that I can see what it's capable of.’” Shoham echoes this sentiment in a way that harkens back to the copier artists of the 1960s and 1970s. As an artist, “if you’re going to use a tool, you're not going to use it the conventional way. You're going to be tasked with trying to make something different with it, trying to figure out how to break it, how to take it apart, how to make it work for you in a different way.” Imagine the creative potential if the companies behind emergent technologies directly supported artists working outside the market constraints of domains such as “entertainment” or “industry,” intentionally breaking the technology and putting it back together again in ways most Unity customers have not yet imagined possible.